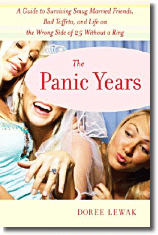

She applied the "Page 99 Test" to her new book, The Panic Years: A Guide to Surviving Smug Married Friends, Bad Taffeta, and Life on the Wrong Side of 25 without a Ring, and reported the following:

Don’t compromise your values, beliefs or ethics in the pursuit of marriage:Read an excerpt from The Panic Years, and learn more about the book and author at The Panic Years website.

Ethics are for suckers, you say? Perhaps. They have no relevance in today’s society? Well, not on my watch, they don’t. Even if you do subscribe to a certain moral code, remember that no PF is worth shelving the inveterate code of ethics you’ve upheld for the past few years, or weeks, of your life. Are you selling yourself short – and compromising your principles – in the interest of landing a PF?

Other No-Nos: Where You Have to Draw the Line:

He claims he’s Seth Green’s half brother.

The above excerpt from p. 99 is certainly representative of the Panic Years experience. When an SPS (or self-pitying spinster) is in the throes of The Panic Years, it’s all too easy for her to discard any and all discretion in the PF (potential fiancé) hunt. Sometimes a panicker doesn’t just lower the bar, but digs deep – really deep – in the hopes of realizing her dream – her diamond engagement bling.

And this is the quintessential quandary of a panicker: she who so badly wants to marry, but checks all good judgment at the door in her effort to hurtle to her “happily ever after.” This unfortunate byproduct of the Panic Years doesn’t dig her out of the Panic quicksand, but conversely it engulfs her even more. Is personality really that pliable? Or, more to the point, should it be for the sake of landing a ill-suited man with whom you have no fundamental connection? Well, the answer depends on the panicker, I guess, but I try to encourage women to be true to themselves. Like usually attracts like in this world, so if you know who you are and stick to your guns on the issues that matter most, the right guy will surface.

--Marshal Zeringue